The Nine-Act Structure of Feature Films

This is nineactstructure.com

This is the definitive Nine-Act Structure page by the originator of the concept, David Siegel.

NOTE: This page is for professional screenwriters and people in the film business. It’s a master class on story structure in 12,000 words and 40+ film clips. If you really spend time understanding this material, it’s somewhere between 5 (intro) and 500 (PhD) hours of work. There are quiz questions at the end.

WARNING: FILM BUFFS, IF YOU READ THIS PAGE FOR TEN MINUTES, YOU WILL FOREVER UNDERSTAND HOW FEATURE FILMS WORK, SIMILAR TO UNDERSTANDING HOW A MAGIC TRICK IS DONE. YOU CANNOT UNLEARN THIS. ENTER AT YOUR OWN RISK.

What is the Nine-Act Structure?

The Nine-Act Structure is a paradigm and a tool for understanding how feature films work. When you read a script, you may be interested in the characters, the theme, the message, the dialogue, etc., but you have to ask whether the story works or not. If the story works, most of the time it follows the Nine-Act Structure.

I would call the Nine-Act Structure a tool, not a prescription. A Google search of “Siegel nine-act structure” turns up many pages and books on narrative structure. I’ve had email interactions with several of these authors who reference my work. Not a single person I’ve communicated with has truly understood the tool. This is my attempt to set the record straight.

A Short History of the Nine-Act Structure

In 1986–90, I spent much of my time learning how movies work. I did it after writing a script that, according to friends, “didn’t work,” and I wanted to find out why. So I rented more than 100 films (VHS tapes), and I watched each one with a stopwatch, taking notes of what happened during each minute of each film. Here’s an example from Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade:

Minutes are on the left; the numbers in the green left-hand column indicate the protagonist’s fortune, so it can be graphed. There are various conventions to indicate montages, flashbacks, songs, etc. There are other pages for characters, analysis, and more. I did this for about eighty films. And I realized that the two-goal plot showed up in the vast majority of commercially successful feature films. I quickly fleshed out the nine acts, and the structure was born.

In 1992, I made a book proposal and my agent sent it to Disney. They sent back a letter saying “It’s a remarkably obsessive piece of work, but we don’t see much of a market for it.” I tried to sell the project to IMDB; they passed. In 1995, I put up several pages on my web site to explain the structure, and that’s where many people found it. Since then, it has been passed around, misunderstood, copied and pasted, and the original work still lives on Archive.org. In the early 2000s, I hired a sharp film geek named Kevin Brooks, and he did another hundred or so movies — I still have all the original files. But I didn’t do anything with the project and got busy with other things. Now it’s available to the world.

I have written many scripts but sent only one to producers. It wasn’t picked up. I’ll link to it at the end.

The Nine Act Structure vs the Three-Act Structure

People don’t understand the Nine-Act Structure, because they are so used to Syd Field and Robert McKee’s story paradigms. The more you have used the traditional three-act structure, the more difficult you will find it to understand my tool. The Nine-Act structure is a much more accurate tool than the three-act structure. If the three-act structure is a magnifying glass, the Nine-Act Structure is a microscope.

The key is to focus on the protagonist’s goal, not on the direction of the action. In a typical script conversation, writers will talk about “reversals” every 20 pages or so, because they want to keep the story changing direction to make it interesting. In my world, you focus on two things: the antagonist’s goal, and the protagonist’s goal, and those two things naturally lead to the train wreck that unfolds between them.

The Two-Goal Structure

At the heart of the Nine-Act Structure is the Two-Goal Structure. Ninety-nine percent of all feature films are either single-goal or two-goal. In both these story types, something (usually bad) happens, and something must be done.

In a single-goal story, it’s clear what must be done, and either a) the right person for the job does the job or b) the wrong person for the job does the job. Or, he/she fails, in which case it’s a tragedy. Either way, I call this a linear plot. A classic example is Nemo. Nemo is the protagonist. Once he is picked up, his goal is to get back home. There are many obstacles, but eventually he finds his dad and goes back to his beloved reef. Most Bond films are linear. Jaws was linear. Cast Away is linear. Mission Impossible 5 is linear, though several other MI films are not. The goal of the protagonist of a linear story is to put the world back the way it was before. Generally, he is changed in the process.

The original Star Wars story is interesting. You might think there are two goals: 1) get the droid to the rebel base, then 2) go destroy the death star. But Leah has laid everything out in her hologram speech at the beginning: bring the droid to the rebel base, where the rebels will look for a weakness they can exploit to destroy the death star. Luke knows that bringing the droid to the rebels is just the first half of the mission. This story has many two-goal attributes but is in fact linear.

In a two-goal story, the hero believes her first goal is the right solution to the current problem, but in fact it’s a trap. This is often referred to as the false goal. Sometimes, she actually attains it, but most of the time she stops short, because she learns what’s really going on and needs a new goal to save the day. Occasionally the hero achieves the second goal and dies in the effort (e.g., Braveheart, Elysium, The Abyss, Titanic) — it’s still a triumph.

In a feature film, there can be at most one false goal. I can only name one film with two false goals — Predator — and I hope it remains the only one, because there’s no room in 110 minutes for three goals and two reversals. Because this is not true for novels, it’s easy to screw up adapting a novel to a film script.

In my world, a reversal is very specific — it’s the moment when the protagonist changes her goal.

Most of the time, the second goal is bigger in scope and much more is at stake than in the false goal. Most of the time, the second goal is to prevent the bad guy’s plan from happening. Examples of two-goal plots:

In the original Rocky, Rocky Balboa thinks he can beat Apollo Creed. He trains and trains, and then he goes to the arena the night before, where he tells Mr Jurgens his shorts are the wrong color in the poster, to which Jurgens replies, “Don’t worry, Rocky, I’m sure you’re going to give everyone a great show.” He realizes he’s been set up. He can’t possibly beat Creed, it’s just a made-for-TV spectacle featuring a local fighter. He vows to “stay standing” for 15 rounds to prove he’s “not just some bum from the neighborhood.” By switching from offense to defense, he most likely saved himself from being knocked out. His new plan changes his character and achieves his new goal.

In Toy Story, Woody’s first goal is to get rid of Buzz, until he realizes that the bad boy Sid is destroying toys and must be stopped. The new plan is kept a secret from the audience.

In E.T., the Extraterrestrial, Elliot’s first goal is to keep E.T. as a friend; his second goal (minute 53 of 107) is to help him get home.

In Jurassic Park, Alan Grant’s first goal is to verify the safety of the park; his second goal (minute 88 of 119) is to get Ellie and the kids to safety after he discovers the dinosaur eggs and the natural tendency for the dinosaurs to get out of control. More than that, his larger second goal is to not verify the safety of the park.

In Home Alone, Kevin’s first goal was to get back together with his family; his second goal (minute 65 of 102) is to defeat the bad guys.

In The Return of the Jedi, Luke’s first goal is to kill Darth Vader and thereby disable the new death star; his second goal (minute 112 of 125) is to kill the Emperor (with the help of his father). Note: death stars tend to be huge and spherical, so they have “normal” gravity inside for shooting scenes.

In Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom, Claire’s goal is to rescue the dinosaurs before the volcano erupts, only to learn that they are being turned into fighting machines and sold to governments and that must be stopped.

In The Fugitive, Richard Kimble’s first goal is to find the one-armed man who killed his wife; his second goal (minute 88 of 124) is to expose his friend Charlie, who was trying to kill Richard in an effort to push Devlin MacGreggor’s new drug, Provasic, through the FDA approval process, making him a rich man.

Similarly, in Monster’s Inc, Mike and Sully go after Boo, only to learn of the evil plan to capture kids and terrorize them (minute 64 of 85), and that the plan “goes all the way to the top.”

In The Silence of the Lambs, Clarice learns that Buffalo Bill is not committing random murders, he’s sewing an outfit of human skin, which turns the plot and gives her the last clue she needs to find him.

In Angels and Demons, Robert Langdon is searching for a murderer, suspecting the Swiss Guards, only to learn that the camarlingo has murdered the Pope in his quest to become the next Pope and rule the Catholic faith.

In Chinatown, Jake Gittes learns that Noah Cross has murdered Mulwray in his plan to create a desert oasis and get extremely rich.

In The Lion King, Simba’s first goal is to forget about the past and live a life of ease; his second goal (minute 60 of 105) is to take his rightful place in the circle of life and be the alpha male.

In Batman, Bruce Wayne’s first goal is to apprehend the Joker and take him to jail for his crimes; his second goal (minute 83 of 118) is to get revenge for the death of his parents by fighting the Joker to the death.

In Beverly Hills Cop, Axel’s first goal is to find out who killed his friend Mike; his second goal (minute 77 of 99) is to bring down Victor Maitland’s illegal arms-smuggling operation.

In Ghostbusters, Peter’s first goal is to go after the ghosts and suck them into the containment vessel; his second goal (minute 72 of 99) is to close the door to the end of the world that the possessed Dana is guarding by eliminating her possessor, Gozer.

In Mrs Doubtfire, Daniel’s first goal is to get his kids back by becoming Mrs Doubtfire; his second goal (minute 98 of 108) is to become the husband and father his wife and family need.

Do you see a pattern here? Going from local to global or temporary to long-term? If you understand this structure, as Aristotle did, you realize that the change of goal is the fulcrum of the film. Aristotle called the reversal “the revelation.” It generally comes between minute 60 and 90. The Nine-Act structure is nothing more than a support structure for a strong reversal.

Obstacles and Complications

In my world, there is at most one reversal per film. Nemo has no reversal. Casablanca has a huge reversal. As the story unfolds, there are obstacles and complications.

An obstacle is something directly in the hero’s path. Nemo meets some sharks and manages not to get eaten. ET drinks beer, get drunk, and Elliot falls asleep in class. Dorothy meets a cowardly lion on the road to Oz. It’s easy to add and subtract obstacles and whammos (a term attributed to Fouad Said) — they are typically 4–6 pages long. You can pad the story with these, and generally they contribute to building the character, exploring the theme, or bringing out the subplot. They really aren’t structural, they are shots of adrenaline with a chance to breathe in between. You should be able to add or take out an obstacle and not change the story at all.

A complication takes the character in a new direction while still in pursuit of his goal. In Toy Story, Buzz jumps on the back of the station wagon and hitches a ride to the restaurant, so Woody has to follow him, and that’s where they are grabbed by Sid, the evil boy. In Tomorrowland, the house has been discovered — they have to destroy the house and blast out of there. In Cars, Lightning McQueen tears up the street in Carburetor Springs and is forced to repave it. In Frozen, when Elsa leaves to go to live on the mountain, Anna pursues her, leaving Hans in charge of the kingdom. That’s not an obstacle, that’s a plot complication. Complications move the plot forward. Without them, the story is weaker.

Complications are second-order elements. If one doesn’t work, use another. If you can think of a better way to develop character while putting tacks in front of your character, switch out. Don’t be attached to obstacles and complications. They may be critical to character, but they aren’t critical to the overall plot. If your script is six pages too long, hack out a complication and tweak the rest.

The Seeds of Conflict: Legitimate vs Illegitimate Reversals

If the reversal is the fulcrum of the plot, it has to be built properly. So to expand on the two-goal plot, we add a few more planks to the platform.

What is the bad guy’s plan? Conflict is central to the plot of any story, and random or superficial conflict is not a driver. For big films, the scale is often global. The mastermind’s plan is often world domination, or market domination, or ruling Gotham City, or something similar. In the play “Dear Evan Hansen,” the antagonist and protagonist are the same person, and the conflict comes when he randomly decides to tell a lie after a character dies. The backstory has nothing to do with it. This feels cheap for a reason — there is nothing at stake.

To have something at stake, both sides need legitimate and strong reasons to do what they are doing. Here we have needs and plans.

Most main characters have a need. A good bad guy has a strong need — often to prove his power over others, or to rule his own kingdom. Voldemort wants revenge over the system that spurned him (this is very common). Harry Potter’s need is to right the wrongs that led to his parents’ deaths and fulfill his destiny as the chosen one (also very common). The Joker wants to have his way with Gotham City. Scar wants to be king of the lion pride. Etc.

While both antagonists and protagonists have needs, it’s the bad guy who always has a plan. If you want to write a screenplay, sit down with a blank piece of paper and ask yourself, “What is the bad guy’s plan?” That is absolutely step one. It must explain how and why he has been executing his plan for years to decades before the story opens. On page 1 or 2, we see the manifestation of this plan as it begins to roll into action after years of preparation. The “bones” of the story are made of the bad guy’s plan. The bad guy’s need to execute his plan is existential for him, and it drives the plot forward.

Once you have the overall plan, you figure out how the plan gets started, how it proceeds, how the protagonist gets sucked in, then how he discovers the plan via the history lesson, which gives him enough information to at least come up with a plausible plan for stopping the big bad thing from happening. Several unpredictable complications later, he manages to do it, but he generally doesn’t need any more strategic information from that point on.

The history lesson is usually 2–6 pages long and occurs on page 65–80, sometimes a bit later. This part of the writing can be done in anywhere from a few hours to a few years.

The history lesson almost always comes at a time when the hero is in the worst shape, at the bottom of his luck, has been set up, and is often captive or in jail. He’s usually in the deepest part of the mastermind’s castle — the control room, the jail, dungeon, throne room, etc. It can be a discovery, an overheard story, an explanation (“Before I kill ya, I’m going to tell you my beautiful plan that I’ve been planning for ten years, muhaha!”), or a third-party explanation. It’s almost never done by a narrator (“What she didn’t know was that he had been planning this for more than ten years …”).

It’s critical that this is the missing piece of information that tells the protagonist what he needs to know. Let’s see some examples …

In Total Recall, the final clue falls into place when Quaid is in Cohagen’s office and sees himself (Hauser) on the screen telling him he’s been set up. He’s been picking up breadcrumbs the entire time, and now he knows he’s in a trap and has to get out. (That scene isn’t online, sorry).

Here’s a more expository style:

The Godfather: Meeting of the Five Families

That’s a tough one, because determining who is the antagonist and who is the protagonist in The Godfather is an advanced exercise, but you can work it out if you know that this scene is the fulcrum of the film. Here’s another classic-style history lesson:

Mr Incredible Learns the Truth

Wall*E: Directive A113

Often, the hero is captive and overhears the master plan. This is the classic scene from The General, where Buster Keaton overhears the enemy plan:

The General under-the-table scene

This is narrative structure: after the history lesson, everything makes sense. Here’s a semi-weak one, but it still works:

The Mask jail scene

In The Mask, the history lesson should really be about Tyrell, the crime boss, and his plan. Instead, he learns some information from after the story starts, which makes for a very weak reversal. The scene motivates Stanley to go stop the bad thing from happening, but it could have been stronger. A good coverage person should flag a weak reversal like this. Gremlins has one of the weakest ones I know:

Gremlins history lesson

This is a history lesson, but it has nothing to do with the main conflict. It explains nothing, it just seemed to Spielberg and Dante like a good idea to stick an emotional history lesson in before the comeback. That’s called an illegitimate reversal.

The Animal House faux history lesson is a classic example of how to turn a plot that has no real bad guy and all the conflict is trivial. Note the historical references because — well, because some kind of history lesson just seems it should be here, but it has no bearing on the actual plot:

Animal House speech

You would think writers could do better than that, but they are following the three-act structure, so it’s understandable that they are confused. It’s fairly common to see a faux history lesson or the message “winners never quit” or some such bromide trying to patch up a weak story line and a weak antagonist (Stephen Spielberg specializes in this). You need something to come between the failure of Act 5 and the comeback of Act 7, so any old history lesson will do. Here’s a better one:

Big — Josh goes back to his old neighborhood

In Big, the antagonist isn’t the Zoltar machine and its maker. The antagonist is Josh, who wanted to be someone else, because he wasn’t happy being a young teenager. That’s why this scene, which reveals information from just before the movie started, actually does turn the story legitimately. It’s not the strongest reversal, because there’s no bad guy planning and toiling for years ahead of time, but if the antagonist and the protagonist are the same person (not the same persona), you can turn the story by explaining why he headed for the false goal in the first place. This scene is enough for Josh to want to go back, which he does, with the help of the Zoltar machine. Becoming big was the false goal. Technically, it’s weak because there isn’t a good bad guy. But it works for a fish-out-of-water comedy.

Casablanca might have the best reversal of all time, watch for the revelation of information from the back story:

Casablanca: I Still Love You

After that, there is a montage in which she tells him everything and says he’ll have to think for all of them now. Remarkably — and this is a huge exception in the canon of the Nine-Act Structure — their time in Paris was only about 18 months ago, not ten years, but in the context of the war that was a lifetime. Here are my notes from that part of the film:

An illegitimate reversal is one where the protagonist’s goal changes for any reason other than learning the bad guy’s long-incubating and unfolding plan.

Sometimes, the hero and the antagonist are the same, as in Groundhog Day. In this case, it’s helpful to think of this person having two personas working against each other, and the “good” one can learn that the bad one has been screwing up his life all this time. There are several variants of this, but the story turns on realizing what a jerk he has been all his life.

Some films, like Apollo 13, Cast Away, Forrest Gump, or The Martian simply have no antagonist. In this case, it’s a fight/race against time, mechanical problems, setbacks, weather, and luck. It’s possible to pull this off with great characters, famous actors, and a relevant premise, but I would say it’s also much more risky at the box office. That’s why most exploratory adventures have a team member who turns out to be the bad guy and whose plan has been to take over the ship or somehow hijack the mission. In Back to the Future, the bad guy is Biff, who threatens Marty’s very existence — this is much more satisfying than going up against physics and weather.

In Jaws, the antagonist is a shark. Sharks don’t make plans! The only way to turn this story is to figure out some mechanical way to defeat the shark, but it’s not nearly as satisfying as foiling bad guys. Jaws is a linear story: bad shark, good guy — both battle, good guy wins. In the Jurassic Park series, there’s always a person and a plan; the dinosaurs are there to make it more dangerous and visual, but the real conflict is human.

I didn’t start my research looking for nine acts. The nine acts simply support a legitimate reversal. So it’s not a complex construction. Rather, the nine acts are required to pull off the reversal properly. I’m not married to the number nine — I’m married to the history lesson changing the protagonist’s goal.

The Nine-Act Structure Overview

A legitimate reversal changes the protagonist’s goal and makes the film much more interesting right at the 2/3 point. This is the recipe for conflict that isn’t predictable. Here is the visual overview:

Act 0: Someone Toils Long into the Night

Act 1: Open with An Establishing Shot

Act 2: Something Bad/Mysterious Happens

Act 3: Meet the Hero

Act 4: Commitment

Act 5: Go for the Wrong Goal

Act 6: Reversal

Act 7: Go for the New Goal

Act 8: Resolution

Film Time vs Story Time

The majority of feature films run100–110 minutes. The story may play out over weeks, months, years, decades. But there’s a remarkable consistency in storytelling: the story most often plays out inside of two weeks:

I give the analogy of the Olympics — participants spend millions of hours in preparation for decades, all of which comes together for two weeks to create a show with a beginning, middle, and end. Because audiences don’t want to see too many goodnights and good mornings, filmmakers try not to have that overhead get in the way. Many films play out over the course of 3–6 days, many go up to a few weeks, to account for travel, falling in love, schedules, events, etc. A month is not uncommon. Longer requires montages and can still work well. Plenty of films cover an entire school year. Sometimes there are great leaps forward in time, but generally that doesn’t change the structure.

Story time is far less than the history of the conflict, and audiences generally don’t want to see huge gaps in the timeline unless they somehow improve the story. So Act 0 is usually ten years long, and acts 1–8 all together are most often 4–14 days.

With that set-up, let’s dive into each act …

Act 0: Someone Toils Long into the Night

Somewhere around 80 percent of all bad guys work on their plan for at least ten years. Eight is short, thirty is long, and some toil away or lie in wait for hundreds or thousands of years until they are ready to spring into action. All this happens before the film starts.

For example, why are the Star Wars series engines of death always spherical, planet-sized space constructions? Because that gives you 1G of gravity inside. What has to be at the core of this man-made planet? Something supermassive, to create the artificial gravity. How long does it take to construct a small planet out of concrete and metal? (Note: magically there is also 1G of gravity inside all spacecraft in the film, which blows the physics.)

It takes time to cook up a good plan and be ready to execute it. Think about real-life crimes — the more serious the crime, the longer it took to plan. If the story is going to have some degree of scale, it will take a while to prepare.

In many conflicts, there is a seminal incident that put the bad guy on his path. It’s very often when someone who is enthusiastic and capable gets passed over for a chance to prove himself, so he goes deep into his bad-guy hideout, builds his power, and doesn’t come out until he’s ready. Other times it’s a random event, an accident, a lost love, etc.

The seminal incident is the thing the protagonist doesn’t learn during the time he’s going for the wrong goal. He learns it in the history lesson. In this light, we can clearly see that Star Wars is a linear plot — all the information we need is already stored in R2D2’s memory. The new information is tactical, not motivational.

The antagonist’s history lesson answers the question why? Why is the bad guy bad? Why is he doing what he’s doing? Why is he so good at it? Why has he started now? The goal of the Nine-Act Structure is to put each person on screen for a legitimate reason.

What to look for: The distinction between backstory and biography. Make sure to distinguish between prehistory — the general background of the place and time, biography — personal histories that add dimension to the characters, and true backstory — the story of the main conflict. Too many stories start with an impactful scene and then dissolve to “Ten years later …” — a sign that the filmmakers don’t have a handle on structure.

Act 1: Open with an establishing shot

Watch movies and you’ll see it over and over. It’s often a crane, helicopter, or some kind of outside-in shot. It’s very rare that the action just starts without this. A favorite of mine:

American Beauty opening scene

I know there’s a little expository shocker in there ahead of time, but the helicopter shot and narrative set the tone.

To save time, many pictures put the Act 1 wider picture behind the credits, so the film can start in the location of Act 2.

Working girl establishing shot

Length: Act 1 is often less than a minute.

What to look for: A crane shot or outside-in shot.

Act 2: Something Bad Happens

This is the beginning of the unfolding of the bad guy’s plan. It’s almost always on the bad guy’s terms — he chooses the time and place. It rarely involves the protagonist, it’s just the first event of more to come. Jurassic Park provides a classic example, giving a taste of what is yet to come:

Jurassic Park, Act 2

Note there is no Act 1, just the words “Isla Nublar” overlaid on the scene, and it works just fine.

In Avatar, the narrator tells us his brother was killed, and we see a body in a box. That’s all. For a classic Act 2, watch The Dark Knight Rises:

Dark Knight opener

This line says it all: “It doesn’t matter who we are. What matters is our plan.”

Here’s a good one:

Despicable Me opener

Sometimes it’s not bad per-se, it’s mysterious:

Jumanji opener

Inglorious Basterds opens with a long but unforgettable Act 2:

Inglourious Basterds chilling opener

Act 2s can vary quite a bit, from a narrative approach to flashbacks to weaving it into the hero’s current life. But in many cases, you’ll see something bad or mysterious happen that foreshadows what’s to come but doesn’t involve the protagonist.

Occasionally, the second act shows something bad from the future, followed by a message saying “X Days Earlier,” and then the story begins. While this worked well in 1973, it’s a cheap way to start a story nowdays (Lego Batman team, are you listening?). Use sparingly.

Obviously, an illegitimate Act 2 would be something randomly bad happening, or something good, or just a character-based scene, not the beginning of the conflict. Here’s a good way to get a story started:

Blue Velvet opener

It’s unusual, because the protagonist discovers the ear, which goes against the Nine-Act recipe, but it obviously works well in Blue Velvet. The Lawrence of Arabia starts with a memorable scene that might look legitimate but isn’t:

Lawrence of Arabia opener

This is the kind of biographical material that should be woven into the main story. It’s not the place to start. The script is based on the biography of T.E. Lawrence, who naturally started his book this way, but following the book outline made the movie unnecessarily longer. Movies aren’t books. When adapting an existing story, look for the first incident that foreshadows the actual conflict.

Lara Croft, Tomb Raider (2018) starts with an exposition about her father, then we see her defeated in the fighting ring, then the story begins. You don’t need all this character work at the beginning of a story, just get it going and weave it in as you go.

Witness starts with a funeral, then Samuel witnesses a murder in a train station bathroom. The murder is one of a string of murders that will lead John Book to uncover corruption deep in the police department. Peter Weir probably could have cut that and improved the film, because it’s Act 5 where we see the strange world the hero must enter.

Length: Act 2 is usually around 5 minutes long, no more than 8.

What to look for: A jolt of action. An incident that is seemingly unrelated to the protagonist but requires more investigation.

Act 3: Meet the Hero

Who is going to fix the problem? Someone who has an unfulfilled need and who just happens to be related to the problem. Seeing Luke Skywalker at home, Indiana Jones teaching, and Rocky collecting debts establishes both a basis for a normal life and the qualifications for extraordinary performance. We learn her need, even if she happens to be lazy, drunk, or unmotivated.

Yet something has happened. Something must be done.

The hero is not the right person for the job. Sometimes, the hero aspires to be the right person, other times she doesn’t. Something has to be done, but she’s not convinced it should be her. The hero often refuses the call, because on short notice she sees no reason to upend her life to solve a mystery. She says forget it, you’ve got the wrong person, I would never do that.

To counteract the refusal of the call, Act 3 typically has three bumps, during which the protagonist accelerates down the tracks toward the take-off point. Each bump puts the protagonist one rung higher on the ladder that leads to the diving board of act 4. I often say “Three bumps and a push,” to help people envision what it takes to get your protagonist over the edge and into the water with the bad guys.

A legitimate act 2 buys about fifteen minutes of character development before the hero commits to her first goal at around minute 20. In Saving Private Ryan, Captain Miller takes the assignment immediately, because it’s his job to do so. In Finding Nemo, it takes Nemo several dares and “bumps” until Nemo is finally scooped up and in the boat of the fish collectors.

In Seven, Detective Somerset is determined to retire and only commits to solving the string of murders when he realizes he is needed.

In Spiderman, Peter Parker goes through many small bumps fighting petty thieves until he realizes that MJ likes Spiderman, at which point he commits to crimefighting.

In The Matrix, we see the classic Nine-Act structure at work. Here is Act 3 with Act 4 at the end (minute 29); you can see the bumps at minutes 12, 14, 19, and 24:

This is also the time to meet the opposing team. While we may have seen some of their work in act 2, it is during this setup-period that we often meet the front man, who does the dirty work of the mastermind. Darth Vader is a classic front man. If we meet the mastermind in this act, we rarely find out he is bad, but we usually understand how powerful he is. In The Fugitive, Charlie the mastermind is Richard’s friend, while the front man, Sykes, looks like the villain.

Length: Act 3 is 4 to 8 minutes long.

What to look for: The hero’s need and the refusal of the call. Dorothy’s need is to satisfy her desire to explore the world beyond the farm. Luke needs to be part of the resistance, not a farmer. Rocky needs to prove himself. This act must lead up to act 4, so it needs to be carefully constructed.

Act 4: Commitment

Most stories have a pretty sharp commitment point. Remember that in most Nine-Act stories, the protagonist commits to the false goal. In The Lion King, Scar and the hyenas convince Simba to run away from his family and community. In Casablanca, Rick commits to learning why Elsa left him in Paris. In The Fugitive, Richard shaves his beard and commits to finding the man who killed his wife. In Mrs Doubtfire, “she” accepts the job offer. In The Incredibles, Bob takes the job working for Mirage. In Alice in Wonderland, she dives down the hole after the rabbit. In Avatar, Jake promises to help Colonel Quaritch by giving him intelligence on the Na’vi.

The Matrix’s red pill/blue pill scene is about as good as it gets for commitment.

The Matrix: Red pill/Blue pill

Here’s another:

“I got friends on the other side” - Princess and the Frog

The two keys about Act 4: 1) there is a cost, and 2) there can be no going back. You should be able to articulate both. It’s practically impossible to find a plot where the commitment point isn’t crystal clear, but it is possible to find stories with weak commitment, where the protagonist could go back if he wanted to.

Length: Act 4 is 10–15 minutes long. It can be shorter, but that’s rare.

What to look for: Three bumps. A good reason the protagonist can’t turn back.

Act 5: Go For the Wrong Goal

It should be obvious to the audience that the hero is now going for the right goal, doing the right thing. If a murder has been committed, the obvious thing to do is find the murderer and bring him to justice. But the bad guy is forcing every move. In most cases, the bad guy drives this act, and the hero is on his heels. In Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid, they keep saying “Wow, those guys are good. Who are those guys?” In Total Recall, Quaid keeps seeing videos he himself left to guide him from one whammo to the next. The hero is playing a game of catch-up, and quality information is scarce. Most often, the front man does the dirty work during Act 5, while the mastermind remains behind the scenes until Act 6.

Act 5 is 40–60 pages. In my view, it has nothing to do with Sid Field’s act 2, though people often confuse them. If you want to learn how to construct an Act 5, watch every episode of the series 24. The best way for a screenwriter to approach all the whammos is to ask: “What’s the worst that can happen?” Make it forced. Make it unpredictable, and make it suck. Make the protagonist pay for her commitment.

During Act 5, the director is busy showing off the premise of the film with set pieces …

Fatboy Slim dance scene

… while the protagonist is busy uncovering bits of backstory that help him learn what’s really going on.

He’s always a minute too late to every whammo …

Angels and Demons murder whammo

Generally, each new clue reveals information from further back in time before the story started.

I call them breadcrumbs. The hero picks up breadcrumbs as he goes, often with no idea how they will figure in later:

The Game: picking up breadcrumbs

Even though the hero can be back on her heels in this act, she can still have fun. In a fish-out-of-water story, this act is where much of the fun is. In a grand adventure story, this is the hero’s journey into the great unknown, where she comes of age and learns, but always at her expense, because she’s in unfamiliar territory.

This is where the fish is out of the water:

Splash — fish out of water

Look for set pieces:

Big FAO Schwarz piano scene

Most of the material of the trailer comes from this act:

Elektra trailer

He’s behind, he’s being watched, he’s outfoxed and outmaneuvered. He’s back on his heels because he doesn’t yet know what’s really going on:

Jack Ryan — hotel-room assault

In many stories, the protagonist is trying to solve a mystery during this act. There is often a series of crimes the hero can’t quite prevent, and each one delivers a new clue:

Clarice gets a clue after autopsy

In the Harry Potter series, Rowling uses the memory vials to take Harry back into the past and reveal information he needs:

Harry Potter — memory of Dumbledore meeting young Tom Riddle

Length: Act 5 is generally around 30–45 minutes long, but in some cases it’s as many as 60.

It helps to understand that Act 5 is the elastic act. You put the other 8 acts in place, then you adjust Act 5 to hit your desired page count. Everything else is “bones.”

What to look for: The hero in a new world, out of his element. This act is where most of the trailer comes from, so you need set pieces that define the story here. Someone, usually a character who is about to die, says “This is much bigger than you think.” The revelation of backstory information in bits and pieces. Flashbacks. The creature in the forest — a magical character who aids the protagonist with cryptic clues and signs. The henchman, who is not the real antagonist, only the servant of the mastermind. Discoveries and complications but no turning point. Entering the lair of the dragon, the deepest point of enemy territory. Jail or capture. Failure.

Act 6: The Reversal

The final puzzle piece falls into place …

The general pattern is that the oldest piece of information is revealed in the history lesson, which tells the tale of the seminal incident:

The seminal incident from Batman revealed in a flashback

In Evan Almighty , God shows Evan his original design without the dam:

Evan Almighty — God shows Evan the original valley without the dam and the houses.

It can be a flashback, but it’s often simply in the form of “Before I kill ya’, I’m going to tell ya’ what happened, why I’m doing this, and how it’s going to work, so you can see how brilliant I am.” We’ve seen many examples above. After Truman has already been gathering clues for several days, the big picture is revealed:

Truman Show reversal

Note that Truman’s reversal comes at the end of the film! There is no Act 7 or Act 8 — they take place off screen later. The film is almost all Act 5! Syd Field would say this film has a three-act structure, but if you use my tool you will understand how this story actually works. Also note that the audience has known this for quite a while, which is unusual but still works.

In Ender’s Game, Ender achieves the false goal, then he goes alone into the Formic’s den to get a short history lesson — that the Formics aren’t really so bad and he’s just destroyed their race, and conveniently their only living pupa is right there for him to take off and find a new home for. The movie ends at the beginning of Act 7, but the history lesson could have been better.

Act 6 usually takes place in the deepest part of the enemy’s territory. In The Mask, Stanley is in jail; in Cohagen’s office, Quaid learns from Hauser he’s been set up; it’s in the golden hall of Smaug, the dragon, where Bilbo learns the dragon’s weakness; in The General, Buster Keaton is under the table of the Confederate officers planning their attack. Many times, he’s held captive in the evil mastermind’s fortress. At this point, it’s clear that he has been set up, he’s been pursuing the wrong goal, and he must turn the tables. It’s all because the history lesson drops the last piece of the puzzle into place.

Here’s one of my favorite legitimate history lessons:

Ghostbusters — Evo Shandor story.

This one is awesome:

Lego Movie history lesson: Finn and the man upstairs

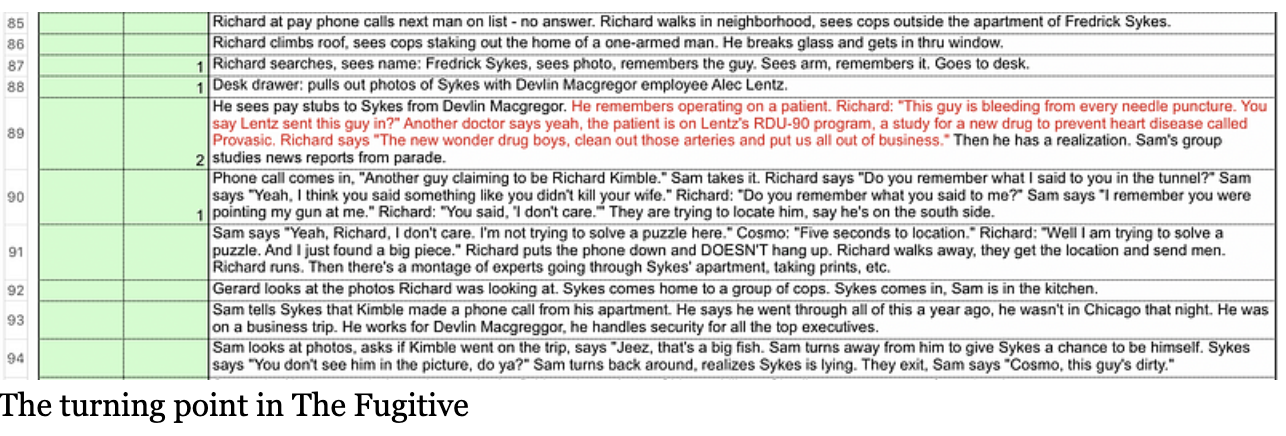

The Lego Movie reversal ties the real world and the Lego world together beautifully. Perhaps my favorite of all time is the turning point in The Fugitive. The scene “Kimball calls Gerard” isn’t online, but it’s in my notes at minute 91:

From this point on: a) Richard is looking for the man who hired the man who killed his wife, and b) Gerard can no longer not care. The story has turned from solving a murder case to solving a major crime against surgery patients and bringing those responsible to justice. Both the protagonist and the cop character change their goals on that single discovery of information from the past (Sykes is the henchman, Charlie is the mastermind).

The key to a good reversal is compactness. Most of the breadcrumbs should have been picked up already. It’s just the last thing that has to fall into place for everything to make sense, and we finally learn the bad guy’s motivation. If there’s a mastermind, he could be revealed or confronted in this scene, but not defeated. He is at the height of his power. He is about to execute the plan he has been dreaming about for so many years. Only one thing can stop him — a hero who knows what’s actually going on for a change.

At the end of this act, which typically takes 4–8 minutes, the hero may or may not know what to do next. She is no longer on her back foot, but she now has to drive toward the solution, usually by escaping the trap first.

Length: Act 6 is usually around 5–8 minutes long.

What to look for: The story or flashback of the seminal incident. The oldest bit of backstory. Everything stopping so the hero can learn the history lesson.

Act 7: Go for the New Goal (the Comeback)

The new goal is clear. The path to the new goal is anything but. The way out of the immediate situation may be clear, or it may be improvised. Very often, there is a secret — a few people whisper to each other what they need to do, and they put their secret plan in motion.

Very often, the first part of Act 7 is a montage of people working on the new plan. This montage generally shows them working feverishly against the ticking clock. It shows that they are getting ready but doesn’t fully disclose the plan.

This act is also called the comeback. The hero is probably starting off in an inferior position, but the nemesis no longer has his built-in advantage. Now it’s a struggle, and the two are evenly matched. There must be the threat of real death for both sides as this epic battle to save the (toys, whales, dinosaurs, cars, city, world) unfolds.

In the world of three-act structure, this act unwinds or resolves the conflict that was built up in act 2. In my view, that doesn’t properly manage the flow of information that changes the protagonist’s goal. You can unwind or resolve pretty much any conflict, but that doesn’t make it believable to the audience. In my world, Act 6 is another one-way door, a second commitment, and there’s no chance to go back. Everything is now on the line and the hero must act.

The most important thing about Act 7 is that it almost never goes according to plan:

Chicken Run Final Escape

Sometimes, the unpredictable part is that what happens is an “exception to the rule.” We see that in Chicken Run and also in The Adjustment Bureau.

There is often a contraption or a sequence of events that has to go just right and has been foretold earlier:

Back to the Future car escape 88 mph

In many cases, there’s a final battle — a mano-a-mano between the hero and the mastermind, often near some very dangerous equipment:

Terminator 1984 final battle

Sometimes you need a new idea, the seed of which was planted earlier:

Croods final battle

Often, an important character is thought dead or missing, then he comes back to life:

Harry Potter final battle

Sometimes, the ranger character, an unallied freelancer (think Han Solo or Aragorn) who went his own way toward the end of Act 5, comes back out of nowhere to help. Often, an important secondary character dies. There is almost always a ticking clock:

Aladdin final battle

Very often, there’s an early climb to the top of a giant structure, so when they fight later it’s life-threatening, and the villain can fall to his death:

In fact, here’s a list of films where the villian falls to his death.

In The Game, Nicholas throws himself over the edge, re-enacting his father’s death.

A ticking clock is usually set during Act 6 or early in Act 7. The ticking clock is usually set for 3–5 minutes. It could be water rising, walls closing in, air running out, etc. It’s always easy to tell how much time the hero has to succeed or die trying. The audience usually sees quite a lot of the clock, and for some reason they always believe the clock could run out before the hero manages to get out of her jam.

The hero is tested severely. He has to use his wits. There is nearly always some reincorporation of elements planted in Act 5. He has to get a little lucky. Yet he emerges victorious in the end, often miraculously, often with the help of a contraption (Deus ex-Machina):

Bugs Life mechanical bird comeback

Then of course, there’s often a double crossing:

Toy Story 3 Final Battle

It’s always personal:

Lion King final battle

Sometimes you just have to do what has to be done:

The Graduate Final Scene

Act 7 is usually the most expensive act to shoot, so build it up and pay it off. Make it visual. Here you can pay off previous easter eggs that result in nice surprises without spending a lot of money (remember The World According to Garp?). Don’t change locations too much, just keep it interesting and use the set, the coreography, and special effects to dazzle between set pieces. In many cases, this sequence takes place on top of a high building or in an industrial setting with lots of physical danger, usually involving gravity, often way over-the-top:

True Lies final battle

In a non-adventure story, the protagonist is changed. He’s learned his lesson. He has the information he needs to be a different person and the comeback is every bit as sweet:

Pretty Woman Knight in shining armor scene

Whether it’s by fighting, outsmarting, escaping, or just changing his ways, the hero prevents the bad outcome and conquers. The worst kind of Act 7 is when the hero undoes the mess he has caused simply by unwinding it and apologizing. The best kind is when he is truly changed and his need is now met:

Groundhog Day - Phil gets the sequence right

Length: Act 7 is almost always the most expensive. It is generally 10 to 15 minutes long.

What to look for: Enlargement of scope. Action. Possibly a montage early on to show preparing the new plan. A secret plan the audience doesn’t know. A ticking clock. Going to the top of a building or other high point so the bad guy can fall down. The see-saw between a credible defeat and an unlikely comeback.

Act 8: Resolution

This act should be mercifully short. No more than four pages. There may be some awards to give, some people to hug and thank, some sacrifices to mourn, talismans to return, rituals to perform, and home to go back to, but it’s okay to leave the audience wanting more. A bit of romance and poignancy go a long way …

Star Wars Throne Room final scene

There’s often a kiss:

The kiss from Groundhog Day

Don’t overdo it. Just boil it down to one final scene that gets most of it done, leave them crying, and then …

FADE OUT

Summary

In essence, the Nine Act Structure manages the flow of information in a film — what the protagonist learns and what the audience learns — to answer all the why questions. The nine acts fall into place naturally to support a two-goal plot. In a film with a linear plot and a single goal, you’ll still see seven acts, because these basic building blocks contribute to a well crafted story. There aren’t many alternatives, really.

My premise is that there are only three kinds of structures:

One goal (we know everything we need to know at the beginning)

Two goal (there’s a spectrum of reversals, from weak to strong)

Shit happens until it’s time to fade out (generally driven by character or premise — I call this a “Nein-Act Structure,” and it’s extremely rare: Shrek, Forrest Gump)

The second goal is generally bigger in scope and importance. It’s precisely because the audience can’t see the second goal coming that the Nine-Act Structure has survived since Ancient Greece. I predict it will be with us as long as audiences enjoy being entertained for 90 to 120 minutes at a time.

Discussion

The Nine-Act Structure answers the question: Why? Why is this happening? Why him? Why are all the characters doing what they are doing? When you have good answers for the why questions, the audience finds the story believable and they want to get involved.

There are many small films that either don’t use the history lesson at all or do it in their own way. In Three Billboards outside of Ebbing, Missouri, the bad guy — Sheriff Willoughby — is bad because he’s lazy, not because he has a plan. So the heroine drives the plot. That’s rare, but there are many interesting variations among smaller films. The bigger the budget, the more likely you’ll see the bad guy’s plan driving a legitimate reversal, because that’s what (unconsciously) gets through the funding process.

Many bad things happen in the real world. There is much drama. There are stock-market crashes, divorces, car accidents, people get cancer, there is gun violence, and there are all kinds of nasty headlines. You can imagine writing a script inspired by all kinds of stories.

But. And this is a biiiiig but.

If no bad guy is planning and scheming for ten years, it won’t be a story that works in a theater. It won’t be worth putting a lot of money behind. Producers won’t jump on it. In every Quentin Tarrantino film, every Cohen Brothers film, every Martin Scorsese film, every Jim Cameron film — the bad guy has been working on it for ten years.

I’ve heard people criticize the structure as being formulaic and prescriptive. This is a misunderstanding. It’s a tool. The few who spend time with this tool understand it as being far more helpful than the standard three acts. There is an infinite variety of ways to modify it, stretch it, and bend it — as I have shown here. Break it if you want to! But if you break it, you should have a good reason, because doing so could limit the size of your audience (or your career as a filmmaker).

What about prologues and epilogues? I think of these as naive additions that first-time writers attach to their stories, probably to increase the page count. In Dances with Wolves, there’s a long scene at the beginning where Dunbar shows his bravery, but it has nothing to do with the plot. First-time writers seem to tack on more endings, just because they can. Or they try to be true to the novel. An experienced writer leaves them crying and rolls the credits.

Several films are very complex and hard to analyze. I can think of Inception, Titanic, Memento, The Wizard of Oz, Curious Case of Benjamin Button, Cloud Atlas, etc. Almost all of these have story-within-story, where each character has two separate roles (or more). The only way to analyze these is to write down the minutes and go through the process. My general approach is to treat each inner story as having its own cast and its own reversal and see if that helps. It’s possible to make different assumptions and come up with different analyses for complex films. I would love to do more formal research on this but don’t have time.

What about novels? Since a novel is an open-ended container, novel writers have more freedom to add more goals. It would be interesting to study novels in the way I’ve done for films. My prediction is that you would see very few linear novels, a lot of two-goal stories, and several three, four, and perhaps even five-goal stories. It’s still the Nine-Act Structure, but with multiple false goals and turning points, until you get to the final Act 6 and everything becomes clear and the hero prevails in the end (or dies trying). I’m not confident that this model of multiple false goals actually describes the vast majority of novels. It’s a hypothesis. But I’m pretty confident that at least half of all popular novels use the same two-goal, nine-act structure I have outlined, as in The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, Platoon, The World According to Garp, Harry Potter, etc. Act 5 can go for hundreds of pages in a serious novel.

What about stage plays? My exposure here is purely anecdotal, but I understand plays better by looking at them through this lens, and I see plenty of history lessons at the beginning of what is traditionally called Act 3 of a play. It would be very interesting to analyze both plays and novels using my tool.

When the good guy is the bad guy

If you’ve gotten this far, you know that the bad guy and his plan drive the plot. But — what if the bad guy turns out to be the good guy? We see this in a few interesting films:

Nine Queens

The Freshman

The Sting

We also see it in the hit series The Money Heist. In Nine Queens, the “protagonist” turns out to be the bad guy, though we don’t learn it until the very end, which I’m guessing is Act 6. In The Freshman, the “protagonist” (Broderick) is tricked into doing the work of the bad guy (Brando), and the bad guy is the good guy. I haven’t seen The Sting recently enough to give an analysis.

If the good guy turns out to be the bad guy, then I think it’s because he’s either going up against corrupt cops, or he’s a “gentleman thief” — the kind who breaks the law but has honor and wants to help others. This is an interesting area I want to explore and compile a list of such films. If anyone wants to help with this, get in touch.

Why No One Talks About This

The Nine-Act Structure based around the history lesson that provides a legitimate reversal has been understood since Aristotle, but it hasn’t been properly formalized. People just feel it intuitively on top of the traditional three-act structure, which is baked into the system. Studio executives will hand back notes saying it doesn’t feel right, it’s the timing, something is off in the second act, the story is too predictable, etc. They “know it when they see it,” because “it works.” The three-act structure is not a very sharp tool for analysis.

Audiences don’t remember the history lessons. After a film with a strong reversal, people will see it as a single story with a beginning, middle, and end. The actual reversal is a fairly quiet scene that mostly gets overshadowed by what comes next. It’s not action, so it doesn’t stay in memory.

John Lasseter, director and producer of so many amazing Pixar feature films, has an intuitive feel for the structure of films. I know John a bit. He’s much more intuitive than analytical. I don’t think he goes into meetings asking for a legitimate history lesson on page 75. I think he’s looking for emotion, complexity, depth, surprise, misdirection, characters doing the opposite of what they say, nuance, and good reasons for each character to be in each scene. I think John has only made one linear film (Nemo); the rest have had the full nine acts.* Here’s the reversal from The Princess and the Frog. It’s in two parts, this is the second (minute 72):

Princess Tiana party

Writers find their way to the Nine-Act Structure intuitively without the tool I have developed, because it simply “works.”

How to Use the Nine-Act Structure

If you have an idea for a film and you want to develop it, take a rigorous approach to writing. Don’t feel your way through the process. I’ve seen too many writers not understand how to edit their material, and they go back and forth, throwing out important structural parts so they can save their darling dialogue or funny bits. Here are my suggestions; feel free to use, abuse, or ignore them …

Films aren’t shot in script order, nor should scripts be written in story order. Use a more agile approach to writing and you’ll end up throwing away much less material. What you need before you even start writing is a good act 0 and a good act 6. Bring me those, and I can put a strong script together. Do it this way, and you will be able to write one or two scripts more per year.

Put the bones down first. You should be able to summarize your nine acts on a single piece of paper. A strong story is built around a good bad guy who has been working on his plan for ten years or more.

Next, work on the backstory. Put all the clues in and really develop the antagonist’s motivation. Get into his head. Understand why the story starts when it does and how that leads to the unfolding of the bad guy’s plan. Be the bad guy for a month or two while you’re doing this. Think about your mastermind and what he needs to build and how long it will take him to do that. Storyboard it. Timeline it. Then figure out who your hero is. Once you are happy with Act 0, you’re ready to begin writing the story (but not the script).

Next, write a treatment of 3–10 pages. Number each act. Get to the core of the story, the characters, and the premise of the film. Edit it. Make it great — this treatment is the seed that grows into your film.

Don’t use scriptwriting software! Use an outliner to write the story, so it’s easy to grab and move things around (a word processor is a distant second choice). Write in prose to start, like you would write a novel, with descriptions and notes and a few key quotes.

Write the hard stuff first. Acts 1, 2, 4, 7, and 8 are easy. Don’t write them first. Write the story using a word processor in this order:

Act 6, 2, 5, 3, 4, 7, 8, 1

Write Act 6 first. Focus on the reversal. There should only be one reversal. Figure out the breadcrumbs that get picked up in Act 5, then write the entire Act 6 before you write anything else. Don’t worry too much about the protagonist, just write the history lesson and make sure it is rock solid.

Then rough out Act 2. Don’t go into too much detail, just choose something that properly gets the bad guy’s plan started, hinting at what is to come. Flesh it out later.

Then rough out Act 5. Act 5 is where the trailer of the movie comes from. (If you don’t believe me, watch trailers and take notes.) It embodies the movie’s theme — if it’s a fish-out-of-water film this is where you see the fish out of water. If it’s femjep, this is where the girl gets kidnapped a couple of times. If it’s romcom, this is where all the memorable scenes like this one are. Because audiences don’t appreciate the reversal, Act 5 is what they will talk about later. The premise, rather than the plot, drives this act — with a few discoveries along the way. It’s often mysterious, fun, and funny at the same time.

Above all, the nemesis is driving and the protagonist is reacting. It should be painful. She’s out of her element. She may trust people who are not trustworthy. She may not see the truck coming. Every ten pages, ask yourself: “What’s the worst that can happen?”

This act has the set pieces. Balance the expense of the production with the impact of the whammos, because this act is where studio accountants can see costs piling up. Be clever and keep this part intriguing and relatively cheap, so they can spend money on Act 7. For example, talk about helicopters in this act, but use them in Act 2 and Act 7.

Act 5 has some special characteristics. As Chris Vogler notes, this act often starts in a new world, a strange world, and it very often starts in a bar (remember the cantina in Mos Eisley or the cabaret in A Bug’s Life), where there are many colorful characters. This should be an unfamiliar world that has its own rules to be discovered. When studio executives talk with you about your film, this is the act they will talk about. But it is the least important structurally!

I say “rough out” because this is the act you should NOT optimize first. You can leave huge holes. A smart way to approach screenwriting is to get Acts 4, 6, and 7 really working and just leave a note for Act 5, saying to yourself “In this act, we start with the protagonist knowing xxx, then we have a bunch of whammos where she learns 1, then 2, then 3, and at the end of this act, she knows yyy:” If you can write that paragraph, your Act 5 is done until everything else is in good shape. Write Act 5 last!

Then write Act 3. Act 3 is character. You’ll get a feel for all the moving parts here, you can introduce the love interest, the henchman, the wizard, and other characters. You’ll probably want the refusal of the call, and you’ll need three bumps — they should tug your protagonist somewhat uncomfortably toward the fight.

Make sure the hero is not the right person for the job. Unless it’s James Bond, no one wants to see the right guy (or gal) for the job do the job. She doesn’t have to be the total opposite, but she should be an underdog or a seemingly unrelated person who gets sucked in — as long as her need is fulfilled by doing the job. Note that the hero’s backstory is almost always part of the plot’s backstory — she is almost never just a random person. If she has incredible strength, wit, ninja skills, and can solve differential matrix equations in her head, make sure her challenges require another skill, like tattooing a bad guy’s chest. Make her improvise, make her suffer, make her struggle, make her fail her way through Act 5. Hit your hero like The Creator hit Truman in Act 5 to keep him guessing. In The Fugitive, Richard really cares about patients and wants to help humanity, but he knows nothing about being a private detective and solving crimes. He has to learn on the job.

Act 4 should be easy now. It shouldn’t be more than a few pages.

Act 7 is easy and fun to write. The hardest thing to do in Act 7 is to keep costs under control. You need to be clever and use resources and reincorporation well.

Act 8 is as short as possible. Make it emotional and roll credits. Don’t tie up all the leftover details. Tie up some, but not everything.

Act 1 should be obvious now. Easier to add at the very end, because you may want to use it to foreshadow what you’ve just worked on.

I’d be careful about using the “secret plan” that the protagonist (and/or his team) have come up with but the audience doesn’t know. I think if you really need it, you probably designed the storyline poorly. It’s very common, and audiences buy it, but I think audiences would prefer to stay with the hero and her POV, because she hasn’t kept any secrets from them before.

Go back and fill in the details. You’re most of the way there. Fill in Act 2, resolve Act 8, adjust the timing and length, etc. Ideally, 4 and 6 are set in stone, and you can adjust everything else easily.

Reincorporate for good mechanics. In act five, the whammos aren’t random. Several of them play a role in the comeback later, though the audience can’t see that at the time. We see this in the Lord of the Rings, Avatar, Ants, and many others.

At this point, you should have about 30-50 pages laid out a bit like a novel, with descriptions, notes, and perhaps a few quoted key lines. Get others to review and give feedback at this stage.

Test it. Get friends to read it. Hold a reading. Find experienced readers and get coverage on your mini-novel. Even though people aren’t used to reading these, they should be. Push people to read this and give you feedback. Adjust if necessary before going on.

Ideally, producers would read these 30-page synopses as submissions, rather than full scripts. If we could get producers to change their ways, we could probably improve the quality of screenwriting dramatically, because it typically takes 60–120 days to write a feature script, then over the course of a week or two, producers pass on it and don’t ever want to see it again.

[David’s dream sequence …

In case anyone is listening, I think writers could write in Final Draft Outliner, flesh out their outlines, test and edit them, and then just share those outlines with producers. A producer would know exactly what she is looking at and would be able to collaborate with the writer at the outline level, then they could discuss an option deal while the writer is turning the outline into a script.

end of dream sequence.]

But that’s not the way Hollywood works, so …

When the story works, fire up Final Draft and write the script! When you like the synopsis, set everything up in Final Draft and write the dialogue last. During this phase, be sure to give each character his/her own voice. I think it helps to work with a friend who can write certain characters’ parts, because it’s too easy to just write dialogue without thinking about what’s in each character’s head and her speech patterns. If you’ve done everything else to prepare, this phase should only take a few weeks, because you’ve already edited the story. This is much faster than deleting hundreds of pages of dialogue that should never have existed in the first place.

When writing the script, I suggest again writing in the same order you wrote the description: Act 6, 2, 5, 3, 4, 7, 8, 1. If you need to adjust the length, do that in Acts 5 and 7, not by adjusting the font size. The font size should be big enough for people in their 50s to read without squinting.

This method lets you make your mistakes easily and cheaply, and it helps you go straight down the middle of the road, rather than veering from side to side.

NOTE: I haven’t gone into all the writing tools, structure tools, and analysis software on the market. I’ll leave you to see if any of those fits well with what I have described here. It’s very possible that some of those tools and methods are more practical and better now than when I last checked.

What to Do Next?

First, use this information. Second, tell people it’s here. It was buried for two decades, and now it finally has a home.

Read The Writer’s Journey, by Chris Vogler. This is the only book I ever really found valuable in my studies of narrative structure. I never found McKee to be valuable, because he cherrypicks his examples to suit his theory. Story Engineering may be good, but I haven’t read it. Same with Aristotle’s Poetics for Screenwriters, which looks interesting.

Keep in mind this is only structure. Character, premise, theme, message, dialogue, and scene mechanics are all outside the Nine Act Structure. I’m giving you a toolkit for building a strong frame — you build your frame and then hang everything on that frame. If nothing else, I hope I’ve given you a way to separate the structure from the rest, so you have a clear head when editing and making changes.

How to Analyze a Film

Follow this recipe:

Don’t rely on memory. Watch the film and write down the action of each minute. At the very least, review the film on video as you work through these steps …

Who is the antagonist and what his his/her plan?

Who is the protagonist? Whose story is it? Could there be more than one? What is his/her need?

What is the commitment? How legitimate is it?

What is the false goal?

How far back in time do the breadcrumbs go?

What turns the story? Describe act 6 in detail. List several possible hypotheses and think each one through. In general, the evidence will lead you to one. How strong is the reversal?

How does act 7 keep the audience guessing?

Write up your full analysis and discuss any deviations from the standard Nine-Act profile.

Quiz Questions

I apologize, these films are dated. If I have time, I’ll add more contemporary questions.

Easy questions

Who is the protagonist in Ratatouille? Who’s the antagonist? What turns the story?

What revelation turns the story in Chinatown?

Are the hallucinations in A Beautiful Mind relevant to the plot?

Analyze Apollo 13 and The Right Stuff.

Analyze Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

Analyze Cool Hand Luke.

Analyze Cars. Who’s the antagonist?

In Saving Private Ryan, what role does Ryan play?

In Tootsie, who is the antagonist? What turns the story?

Analyze Thelma and Louise.

Analyze War Games.

Analyze When Harry Met Sally.

Analyze Analyze This.

Analyze How it Ends.

Analyze Parenthood.

Analyze The Martian.

Analyze Finding Nemo: Why is Marvin not the protagonist?

Medium-hard questions

In the world of the Nine-Act Structure, what’s the definition of a tragedy?

Who is the protagonist in Psycho?

American Beauty starts with a little shocker. Imagine how you could work that into the film rather than putting it at the beginning. Can you find a better solution, or do you think they way they did it is optimal?

Analyze Casablanca.

Analyze Rain Man.

In Jurassic Park, who is the antagonist?

In Total Recall, what role does Hauser play? Who is the mastermind?

Analyze Ocean’s Eleven.

Analyze The Sting.

Analyze Natural Born Killers.

Analyze Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.

Analyze Lara Croft, Tomb Raider.

Compare the structures of Beverly Hills Cop I and II.

Analyze Catch Me if you Can.

Analyze Fatal Attraction.

Compare my analysis of Rocky with a three-act analysis.

Compare my analysis of The Truman Show with a three-act analysis.

Piece together Casablanca. It’s fun and interesting.

Analyze Angel Heart.

Analyze The Wrestler.

Analyze Shrek I and II — how do they compare structurally?

At least two films I’ve mentioned on this page end at Act 6. What other films end at Act 6? Discuss why they are this way.

Hard questions

Who is the protagonist in The Godfather? Who is the antagonist?

Analyze The Wizard of Oz (very advanced).

From the above question — how do you deal with story-within-a-story? Can you generalize this? Does my recursive theory hold for stories-within-stories?

Look at adaptations from novels to films and try to learn how the Nine-Act structure may apply to both. Try analyzing the film Adaptation.

In Gone with the Wind, who is the protagonist? What is the turning point?

In Apocalypse Now, what is Willard’s need? What are his two goals? Who is the antagonist?

Analyze Toy Story (Who’s the protagonist? Who is the antagonist? What are their goals? What turns the story? See note **).

From the above, can you generalize a buddy-film protagonist formula using the Nine-Act framework?

Analyze all Pixar films and discuss their structures against each other (Include The Princess and the Frog).

Analyze The Sixth Sense. Who is the protagonist? What is unusual about Act 5? Can you imagine a way to improve this?

Analyze Titanic. (very advanced)

Analyze Fantasia.

Are there structural similarities among films where the protagonist is also the antagonist? Can we generalize anything about these films and their structures?

Are there good examples with two antagonists, or a story-within-a-story where each level has its own antagonist? This is something I haven’t researched.

Quotes

“David Siegel, with his concept of the 9-Act Story Structure, has opened my eyes and my thinking about how stories function on the deepest levels, and how they can be told for the greatest audience impact. Writers: don’t limit yourself to 3-act structure! The 9-Act Story Structure points the way!”

— Lee Matthias, Lateral Screenwriting — Using the Power of Lateral Thinking to Write Great Movies.

Epilogue

I don’t plan to update this page much, but I do hope people will use my work and acknowledge my contribution. It will be interesting to see how other people incorporate this work into their theories, structures, and consulting.

If you find a mistake or a dead link, please let me know.

I won’t allow comments. If someone wants to set up a Slack or Reddit or community to discuss this, I’ll gladly point to it from here, just let me know.

If you want me to help you with your script — I can’t, I’m sorry, I’m far too busy.

I don’t have time to answer questions about this material.

If somehow you want to help move this project forward or make it useful in some commercial way, contact me. I am interested in consulting for studios, producers, and directors as time permits.

If you have an academic interest and think you could get funding for research along these lines, definitely contact me. Ideally, someone will help me put a few thousand films into a database, then we can use data science and look for interesting insights.

If you have a page on story structure, I’m not going to link to it. I don’t have time to maintain a list of links and resources, sorry. If you mention me, please give me proper credit and link to nineactstructure.com.

If you want to develop a resources page that complements this, I’ll gladly link to it.

I’m david at dsiegel.com. Please accept my apologies in advance if you try to contact me and I don’t get back to you.

Oh, my script? It’s called Run Sid Run. You’ll have to ask me for it.

*In 1986, I worked for Pixar. In about 1992, I met with Ed Catmull to explain my research on the Nine Act Structure. He said it wouldn’t apply to Toy Story, because it was “a buddy picture.” I was disappointed that he didn’t ask me to do some consulting and research on the Toy Story script, but they didn’t need me to help them craft a script that already had all nine acts, like clockwork.

** There are different interpretations of Toy Story, depending on who you see as protagonist and antagonist. My view is that Woody is the protagonist and Buzz is the sidekick. Woody’s first goal is to get rid of Buzz, but that’s a false goal. His real goal is to vanquish Sid, the evil mastermind who tortures toys. After they accomplish that, it’s a matter of getting back to Andy and his family. Two unusual things: 1) the arrival of Buzz does not portend the future conflict, and 2) Act 8 is very long and cliff-hanging. Other interpretations are possible. Kevin B says Woody and Buzz are co-protagonists and their single goal is to stay with Andy. Another point is that Buzz has his own back-story revelation and reversal. The point of my tool is to have intelligent conversations around such views.

This material is copyright © David Siegel 2023. Do not take or distribute this work; link to it instead.

David Siegel is an American serial entrepreneur living in Washington, DC. The only company he’s ever worked for that he didn’t start is Pixar, in 1986. He is the founder of the Pillar project. His full bio is at dsiegel.com.

If you liked this, explore this site — there’s a lot here.