The Machine Economy is

Coming — We are Not Prepared

We are living in a brief period before machines take over. It is akin to the period when motor power took over human labor — no one will remember it. The upside outweighs the downside by a large margin. Unless, of course, it doesn't.

In this short essay, I ask you to think differently about technology, employment, economics, and the future. It’s based on a book I want to write, but a large publisher said don’t bother because books about the future don’t sell very well. Here’s the mock-up of the cover:

This is just a mock-up. The book doesn’t exist, I don’t know Malcolm Gladwell, and he never said that.

I want to make two important points:

We are living in a remarkably brief transition period between two dominant economic eras.

We are acting as if this transition period is the future. It isn’t.

Most of what we’re doing today is not preparing us for a reality that is just around the corner.

Transition to the Machine Economy

From the beginning of civilization, humans communicated and did business with other humans. Then various organizations sprang up — tribes, religions, governments, corporations, projects, associations. These all had human representatives with written codes of behavior.

In the past 150 years, humans have begun interacting with machines. In the past 40 years or so, our machines have become “smart.” They have “human interfaces” designed to let our fingers, voices, mouse clicks, and keystrokes give information to machines. Now we can shoot photos and videos, edit them, navigate our cars, order food, and do many other useful things on screens designed to let humans do more work in less time. Recently, we have started to interact with “intelligent machines.”

For example, cars and trucks can now drive themselves, but they have to do so on the highway full of human drivers. They have to be aware that anything can happen, because humans are behind the wheel of most other vehicles. And humans are not very good drivers.

Isn’t that adorable?

That’s what they’ll say fifty years from now, because we’ll have transitioned fully to the machine economy by then. We’re about twenty percent of the way to the machine economy now. By 2050 or sooner, we’ll be eighty percent of the way. A tipping point will come, and it will change everything.

Most people assume we are coming into the “smart digital age,” where our tools are digital and they help us do what we want to do. We think of ourselves as drivers and pilots. We think our driver and pilot licenses will be digital, residing in mobile-phone apps. We think apps will continue to give us more power, and human-computer interfaces will continue to improve.

Adorable.

But wrong.

In the machine economy, my agents negotiate with your agents and with potentially millions of other agents to help me get what I want. Some agents will exist simply to get what they want. Humans won’t be allowed to drive cars, because all the cars will communicate with each other in real-time. They will share information, goals, and strategies. They can cooperate and optimize. For example, they can all drive at highway speeds with a separation of one car-length. They can let emergency vehicles through easily. They can monitor sensors in cars, on the road, around town, even in the sky. They can prevent accidents. All cars know the road and traffic conditions many kilometers ahead all the time. They can manage congestion on alternate routes or weather events coming in the near future. They might accept payment for giving others priority, and they can much more efficiently plan the daily commute, perhaps even preventing you from getting onto the road until the time is right. A car may be a legal entity and work for itself or work for another car. The million annual US highway deaths will be reduced to a few thousand. When you fly in a drone, you’ll say where you want to go and the drone will negotiate with thousands of other vehicles in the air to get you there safely. By itself.

There won’t be any pilots.

In the machine economy, machines have no interest in playing chess with humans.

Wage Polarization

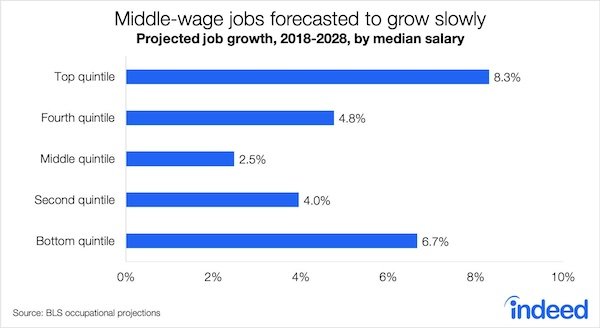

Very little wage data is available from before 2018, so instead, let’s look at this forecast from Indeed:

This is in line with many studies showing that high- and low-wage jobs have generally increased, while middle-wage jobs are being eaten by software and machines. The way I explain it is that high- and low-paying jobs are simply those that robots and software don’t feel like doing yet. Middle-paying jobs give them more bang for their buck. We used to think this would happen gradually. Now it is accelerating.

Any repetitive task will be automated. Today, AI is a smart undergraduate student that can fetch data and answer questions. ChatGPT has scored 90 percent on the bar exam for lawyers. But the orders of magnitude are coming fast. In five years, it should be at or above the level of all the smartest people on earth. Over time, machines will take on jobs that are mostly, but not completely, repetitive. In ten years or so, AI will have a big advantage over most doctors, since they can 1) read every paper (skeptically), 2) review millions of cases and outcomes, 3) confer with thousands of other robodocs and specialists, and 4) do Bayesian calculations to decide what to do next. Not only will Picasso and Matisse return in the form of algorithms and paint their next paintings, they will also feed off each other and continue to evolve their styles in light of other algorithms also painting contemporaneously. Rather than being a tool, AI will soon do many creative jobs as well.

This is not going to stop.

I believe there will be plenty of jobs in most places. They just haven’t been invented yet.

Technological Redeployment

Gradually — and then suddenly — almost every area of human endeavor will eventually find itself in a machine-dominated economy. Don’t be scared when people say 20–40 percent of jobs today will disappear in twenty years — that’s always the case, and there are always plenty of new jobs on the horizon.

We should welcome the progress and the quality of life AI brings. We don’t set bowling pins by hand. We don’t use white-out on the typewriter. We don’t use paper maps. Our phones aren’t mounted on the wall. Do you want the cords back? Every time there has been an advance in technology, new jobs came along, more jobs were created, and quality of life rose as a result. We may be uncomfortable about big companies dominating our digital lives, but I don’t think any of us wants to give up our smart phones or our Google services or Amazon to fix the problem.

It is not going to be a gradual transition to a world of humans and machines interacting. It’s going to be a bulldozer taking all the repetitive jobs first and then getting creative and taking on new challenges, possibly even asking for citizenship and the right to vote. If you read Robin Hanson’s book The Age of Em, (warning — technical and amazing), it’s just a matter of decades until one hundred percent of human work is done by machines (including writing, funding, producing, marketing, and performing in films, concerts, and live entertainment). Robot magicians and entertainers of all kinds are coming. They may even make enough money to invest in more.

The machine economy will develop very unevenly. We’ll see more of it in big cities than in rural areas. Robots will keep picking off the next easiest jobs, which means what you see in an Amazon warehouse or Tesla factory today you’ll see in Nairobi in ten years or so. Think less about geography or scale; think more in terms of access to computing resources and connectivity.

Risks

There are absolutely risks to massive adoption of AI. When we delegate our tasks to AI, we hope AI is aligned with our values even more than our goals. Those worried about AI risk make a simple argument: if the risk of total societal annihilation is 1 percent per year, then it’s just a matter of when, not if.

However, what is the risk of either trying to restrict AI or having no AI at all? We can’t put the genie back into the bottle. One way to “make AI safe” is to set up government regulations, or even nationalize the technology. Leopold Aschenbrenner claims AI is too important for the national security apparatus not to get involved in a big way:

The genie is already out. Companies and nations are mobilizing every resource to accelerate AI. Regulatory capture is likely, but if they turn every programmer into a criminal they won’t have big enough jails to fill with people who have ideas about improving AI systems. Yet governments aren’t going to sit by and watch. In my view, governments pose as big a threat as AI itself does.

Then there’s the threat of not having AI. What’s so safe about the world without AI? What are the chances of something very bad happening each year without AI?

The questions are moot. AI is coming. What can be done will be done, whether it’s legal or not. We are soon going to be behind our technology.

But we can catch up.

The Giordano Bruno Institute

I propose a solution: a complete overhaul of the way we use our own personal data, which I think will lead to rebooting the human operating system. Because I don’t think we want to go forward into the future with all our data on the servers of a handful of large multinational companies. I think automation is good, but centralization is going to make us all more vulnerable.

We should be asking — how can we be more decentralized, more autonomous, less fragile? How can we be more driven by reality and data than our own biases and biological handicaps? Our thinking, our way of doing things, the way we solve problems and ask questions, our frameworks for understanding the world are in need of a serious overhaul. That’s exactly what I propose to do over the next twenty years. Here are my plans to create a new operating system for humans in the 21st century …

Learn more at the Giordano Bruno Institute.

Summary

The next thirty years will be seen as a blip in human history, an awkward pause before the machine economy arrives and settles in for good. Any child born after about 2040 won’t remember the human-to-machine economy. There will still be plenty of jobs, but they will be different from the jobs we know today. People will probably be far better off than they are today, just as we are much better off than we were thirty years ago.

Tyler Cowen, in his book Stubborn Attachments, says:

… individuals who will live in the future should be less distant from us, in moral terms, than many people currently believe. Their interests should hold greater sway over our calculations, and that means we should invest more in the future.

If you like this, read my blog post “We are Now Entering a Period of Accelerating Stupidity.”

David Siegel is a serial entrepreneur in Washington, DC. He is the founder of the Pillar Project and 2030. He is the author of The Token Handbook, Open Stanford, The Culture Deck, Climate Curious, and The Nine Act Structure. He gives speeches to audiences around the world — see his speaker page if you would like him to speak at your next event. His full body of work is at dsiegel.com.